By: Robert Hawley, Associate Professor in Earth Sciences at Dartmouth College and Kelly Brunt, Associate Research Scientist with Earth System Science Interdisciplinary Center at the University of Maryland

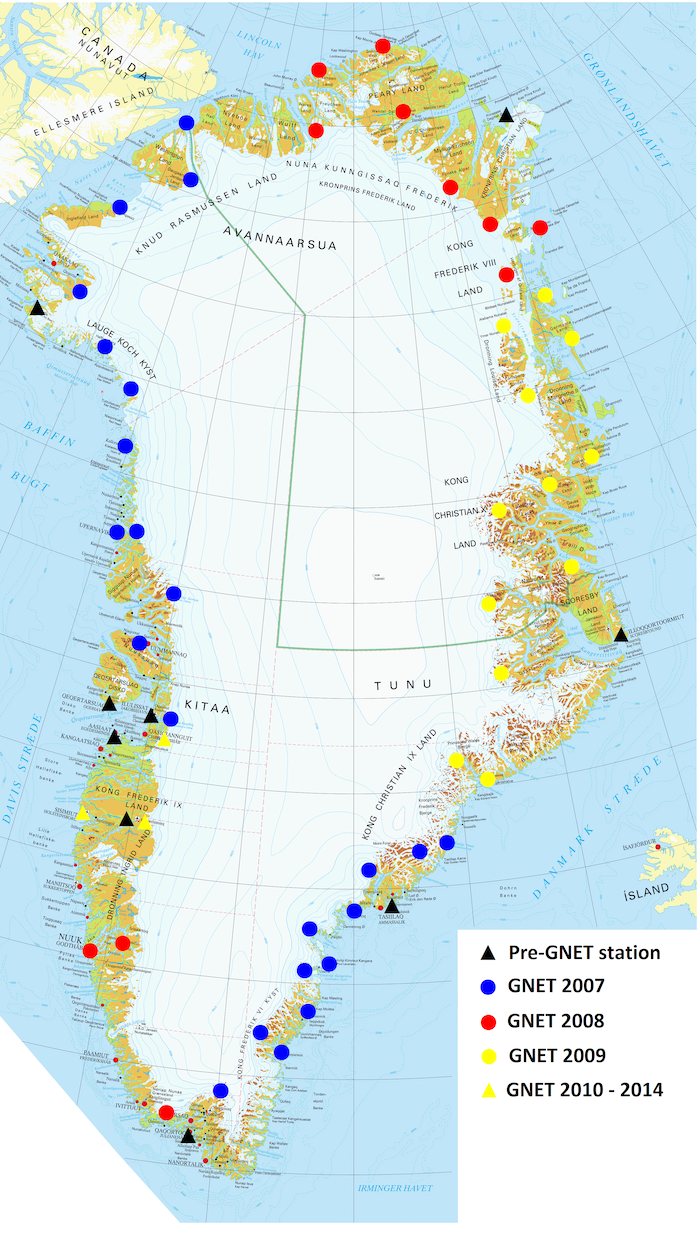

The Greenland Geodetic Network (GNET) is a series of global navigation satellite system (GNSS) installations located on the bedrock exposed around the perimeter of the island. The network is jointly managed by the United States and Denmark. The initial network was conceived as part of the Polar Earth Observing Network (POLENET), an International Polar Year (IPY) project, aimed at observing the polar regions, predominantly through the use of GNSS and seismologic systems. This network maps vertical and horizontal movement of Greenland, over time, to help improve our understanding of ice-mass changes, allowing scientists to quickly detect and analyze any abrupt changes in the rate of ice loss in this region.

GNET currently consists of 58 stations, deployed predominantly by the NSF and in conjunction with other various international stakeholders. The most prominent institutions involved in supporting this effort have been Ohio State University, the University of Luxembourg, the University Navstar Consortium (UNAVCO, Boulder, CO), and the Institut for Rumsforskning og Rumteknologi (DTU Space, Copenhagen). The network was originally devised for geodesy and solid earth geophysics research, with the intent of measuring millimeter changes in crustal height. However, an ever-growing science community, including ice-sheet mass balance studies and ionosphere and troposphere research, has subsequently used these high-precision measurements. To date, GNET data have served a variety of useful scientific purposes, for example: solid earth and isostatic adjustment (e.g., Bevis et al. 2012); large-scale geodesy (e.g., Bevis et al. 2013); ice-mass balance (e.g., Khan et al. 2010), and more specifically surface mass balance (e.g., Liu et al. 2017); support of remote-sensing mass balance missions (e.g., Khan et al., 2016); and ionosphere and troposphere research (e.g., Durgonics et al. 2017). Several recent efforts that used GNET in investigating properties of the Greenland ice sheet are listed on the GNET Publications webpage.

In January 2019, NSF and the Danish Agency for Data Supply and Efficiency (SDFE) signed a memorandum of understanding formally handing over ownership and maintenance responsibility for GNET to the Danish government and SDFE, thus securing the continued operation, maintenance, and upgrade of the network. Under the agreement, NSF continues to supply SIM cards for data transfer and maintains a role in the Steering Committee to guide changes and updates to the network. Under the agreement, SDFE has committed to ensuring free and open low-latency data access for raw and processed GNSS time-series.

The new governance structure for GNET consists of three groups. The Steering Committee is the decision-making body for GNET operations, maintenance, and upgrades, and consists of representatives from funding agencies NSF and SDFE, and DTU Space. The Advisory Board provides expert science guidance to the Steering Committee, to ensure decisions made on the network reflect the current and future needs of the science community and users of the network. Members of the Advisory Board include researchers representing the different disciplines using GNET data. Finally, the Operational Team is a small group that carries out the required maintenance, installation, and upgrades to the network under the guidance of the Steering Committee.

To encourage innovative and new uses of these data and to encourage new, potentially interdisciplinary, scientific collaborations that use these data, NSF funded a GNET Research Networking Activity (RNA). The objective of these activities is to make GNET data more accessible to researchers with the express purpose of fostering new and interesting science and innovative use of these data, and to engage the science community to pose new questions associated with these data.

As part of this RNA we have created a new GNET website to act as a clearinghouse for all GNET-related information and data. We encourage anyone interested to visit this website for more information about the network, the data, and how to get involved with GNET.

References

Bevis, M., J. Wahr, S. Khan, F. Madsen, A. Brown, M. Willis, E. Kendrick, P. Knudsen, J. Box, T. van Dam, D. Caccamise II, B. Johns, T. Nylen, R. Abbott, S. White, J. Miner, R. Forsberg, H. Zhoua, J. Wang, T. Wilson, D. Bromwich, and O. Francis. 2012. Bedrock displacements on Greenland driven by ice mass variations, climate cycles and climate change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109, 11,944–11,948, doi:10.1073/pnas.1204664109.

Bevis, M., A. Brown, and E. Kendrick. 2013. Devising stable geometrical reference frames for use in geodetic studies of vertical crustal motion. Journal of Geodesy, 87(4): 311–321, doi:10.1007/s00190-012-0600-5.

Durgonics, T., A. Komjathy, O. Verkhoglyadova, E. Shume, H. Benzon, A. Mannucci, M. Butala, P. Høeg, and R. Langley. 2017. Multiinstrument observations of a geomagnetic storm and its effects on the Arctic ionosphere: A case study of the 19 February 2014 storm. Radio Science, 52(1): 146–165, doi:10.1002/2016RS006106.

Hawley, R., and 25 others. 2017. Report from the NSF workshop: GNET 2017 forward: The future shape of a Greenland GNSS observation network, January 26–27, 2017, Greenbelt, MD, 37 pages.

Khan, S., J. Wahr, M. Bevis, I. Velicogna, and E. Kendrick. 2010. Spread of ice mass loss into northwest Greenland observed by GRACE and GPS. Geophysical Research Letters, 37, L06501, doi:10.1029/2010GL042460.

Khan, S., I. Sasgen, M. Bevis, T. van Dam, J. Bamber, J. Wahr, M. Willis, K. Kjaer, B. Wouters, V. Helm, B. Csatho, K. Fleming, A. Bjork, A. Aschwanden, P. Knudsen, and P. Kulpers Munneke. 2016. Geodetic measurements reveal similarities between post–Last Glacial Maximum and present-day mass loss from the Greenland ice sheet. Science advances, 2(9): e1600931.

Liu, L., S. A. Khan, T. Dam, J. H. Y. Ma, and M. Bevis. (2017). Annual variations in GPS‐measured vertical displacements near Upernavik Isstrøm (Greenland) and contributions from surface mass loading. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 122(1): 677-691, doi: 10.1002/2016JB013494.

About the Authors

Robert Hawley is an Associate Professor in Earth Sciences at Dartmouth College. He is a glaciologist with a focus on ice-sheet physical processes. He received his PhD in Geophysics from the University of Washington in 2005. Since 1995, he has conducted glaciological fieldwork on Greenland, east and west Antarctica, Svalbard, and mountain glaciers in North America.

Robert Hawley is an Associate Professor in Earth Sciences at Dartmouth College. He is a glaciologist with a focus on ice-sheet physical processes. He received his PhD in Geophysics from the University of Washington in 2005. Since 1995, he has conducted glaciological fieldwork on Greenland, east and west Antarctica, Svalbard, and mountain glaciers in North America.

Kelly Brunt is an Associate Research Scientist with Earth System Science Interdisciplinary Center at the University of Maryland and the NASA Cryospheric Sciences Laboratory. She received her PhD in Geophysics from the University of Chicago in 2008, modeling ice-shelf flow and the connection between ice shelves and the ocean. She is part of the ICESat-2 mission, and is working on post-launch validation of the satellite elevation data.

Kelly Brunt is an Associate Research Scientist with Earth System Science Interdisciplinary Center at the University of Maryland and the NASA Cryospheric Sciences Laboratory. She received her PhD in Geophysics from the University of Chicago in 2008, modeling ice-shelf flow and the connection between ice shelves and the ocean. She is part of the ICESat-2 mission, and is working on post-launch validation of the satellite elevation data.